The Investment Paradox of Software

“Distinguishing a paradigm shift from a temporary cycle is what separates good investors from momentarily lucky investors”

Morgan Housel, Collaborative Fund

“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it's about the future”

Niels Bohr

I. Introduction

The period 2014 to the present has been one of soul-searching for value investors as many formerly successful fund managers retire following stagnant performance. Commenters increasingly describe a market rally that is remarkably narrow in breadth led by FANG (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google) and other software-driven technology stocks which trade at valuations which appear unhinged from traditional cash-flow based valuation metrics. There are several possible explanations for value investors' under-performance: more competitive markets, diminished information asymmetries, a venture capital bubble, or changes in business models, especially in terms of technology and intangible assets. Yet, there is also some historical evidence that our current tech-dominated market indexes may simply reflect the out-sized importance of software in emerging business models.

If part of our job as investors is to navigate changing markets then it behooves us to ask what might of changed. There have been important changes wrought by software on the structure of the economy and business. Some of the implications were first surfaced in Marc Andreessen’s 2011 essay Why Software is Eating the World.

With software being a relatively new business model does it conform to the same micro-economic assumptions that historically underpinned value investing such as diminishing returns and regression to the mean? Conversely, if this theory of software is wrong, understanding – and disproving – these misconceptions might prove useful for value investors’ ability to stay the course.

This essay reflects my own attempts to reconcile a value investors belief in the sanctity of cash flow valuations with the paradigm-shifting implications of software on the economics of business. If the folly of the dot-com bust in 2000 was an inability to bridge the creative measurement of consumer eyeballs with future realizable cash flows, this essay attempts to connect current high market valuations, through the micro-economics of software, to reasonable cash-flow based valuations.

This essay has four parts. First, I present some evidence that market valuations are context-specific to our ability to forecast the future: as our forecasts & information improve, investors can justify higher valuation multiples (lower discount rates). Second, I discuss micro-economic features of software-driven businesses such as incremental margins, network effects, and newer data- & model-driven effects. Third, the combination of these features might drive increasing returns to scale (as opposed to diminishing returns to scale and mean-reversion). Last, I briefly discuss the investment implications one of which, paradoxically, is that investors might be willing to invest in high cash-flow multiple stocks, rather than low-multiple stocks, reflecting a software businesses’ higher sales growth driving an increased probability of eventually dominating their markets.

Ultimately this topic is too large for a few pages. Future essays will discuss some specific investment implications from the viability of certain stock-picking strategies to the potential performance divergence between listed securities in emerging and developed markets.

II. Investing is the reduction of future uncertainty

Investing at its simplest can be described as the reduction of future uncertainty with risk described as “more things can happen than will happen” [3]. Using a mosaic of information investors must decide which of those future outcomes is most likely and discount it appropriately. A natural corollary is that as technology and information reduce investors’ uncertainty in the future, higher valuation multiples (and lower discount rates) might be warranted.

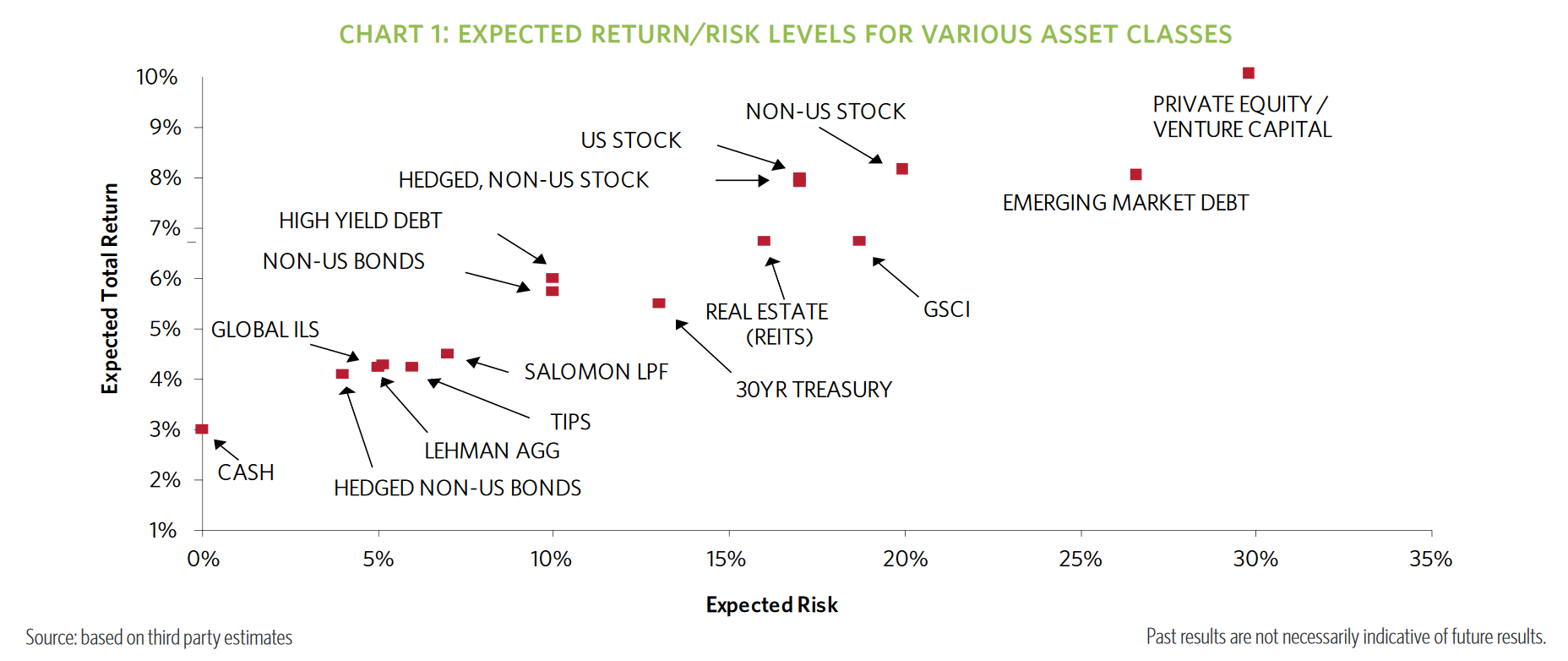

For instance, a US treasury bond entitles provides a highly-certain stream of future bond coupons and therefore provides a lower yield than equity investments with higher uncertainty. Similarly, consumer staples stocks typically trade for higher p/e multiples than cyclical industrials. The risk-curve below illustrates this trade-off between expected total return and expected risk (volatility / uncertainty) of various asset-classes:

III. Valuation paradigms are not static but have changed over-time

In my estimation there have been three significant shifts in how market participants have discounted future uncertainty. In each case it appears these changes occurred at points of inflection in information availability, technology and the mental frameworks investors deployed to reduce the uncertainty of the future:

1932 - “Is American business worth more dead than alive?” Benjamin Graham, Forbes Magazine

After the Great Depression American companies regularly traded below their net current asset value (shorthand for business liquidation value) reflecting extreme uncertainty, minimal corporate disclosure, and general market malaise. Unrecognized value might seem obvious to contemporaries but likely ignored an important lack of reliable corporate information during that period. As Charles Ellis, the founder of Greenwich Associates, described even by the 1960’s & 70’s securities analysts knew precious little about company fundamentals of listed stocks. Buffett, Munger and Bill Ruane were examples of individuals whose out-performance perhaps reflected a knowledge of Graham’s framework of valuation combined with a tenacity to seek additional local sources of information, generally unavailable to most market participants, to move beyond the limitations of existing corporate disclosures.

1972 - Munger & Buffett’s purchase of See’s Candies at 15x P/E and 3x book value

Warren Buffett’s purchase of See’s Candy in 1972 signaled a drastic shift in the relationship between cash-flow multiples and uncertainty, a perspective the world’s foremost value investor only reluctantly embraced. Charlie Munger, and then Buffett, identified that competitive moats and reinvestment opportunity characterized a certain type of ‘quality’ business whose future could be more accurately forecast than most, thus deserving a higher valuation multiple. Buffett and Munger also recognized that this framework applied to only a minority of publicly-listed businesses.

2014 – A world without widgets: Information goods, software businesses and increasing returns to scale

The recognition that not all business models conform to the dominant theories of diminishing returns to scale and regression to the mean was evident long ago. Tim Wu, a Columbia Law School antitrust professor, wrote an excellent introduction to the topic in his book The Master Switch about the history of information goods over the last 100-years. More recently, in the early-1980’s W. Brian Arthur of Stanford University and Santa Fe Institute began writing about network effects in information businesses such as Microsoft and VHS / Beta. This framework of ‘increasing returns to scale’ may have important implications for investors’ ability to predict the future, in the same way Munger/Buffett’s ideas of ‘quality’ allowed them to move beyond asset-based investing.

Interestingly, many of the investors who insightfully recognized the early-value of software-driven businesses such as Amazon.com were also associated with the Santa Fe Institute / W. Brian Arthur including Bill Miller and Michael Mauboussin of Legg Mason Capital Management, and Nicholas Sleep of Nomad Partners.

IV. What might explain the predictability of software-driven businesses?

We hypothesize that dominant software-driven businesses may be more predictable than many other types of businesses. If so, how do we reconcile the micro-economic study of the software business with the predictability we envisage?

The characteristics of software businesses can be categorized into four areas: (i) incremental economics; (ii) incorrect heuristics; (iii) data / model-dependent businesses magnify network effects; (iv) insufficient disclosure for investors to evaluate intangibles.

Economic characteristics of software-driven businesses

On a simplistic basis discounted cash flow models have four inputs: (i) profits, (ii) timing, (iii) duration, and (iv) quality of data. There are arguments that these variables are extensively changed by software.

Profits: Software is characterized by high initial fixed costs but zero marginal costs and high incremental profit margins. Profits can inflect quickly, changing from an unprofitable business to a very profitable business once break-even is reached.

Timing: Scaling an internet software business on rented AWS IaaS (Amazon Web services Infrastructure-as-a-Service) happens more quickly and at a lower cost than almost any other business model the world has ever seen. The graphic below from Upfront Ventures illustrates this point:

Duration: Increasing returns to scale and network effects describe businesses where the probability of business longevity increases (not decreases) with size. Paradoxically, if true, it would make successful, fast-growing companies more valuable than slower-growing companies. In addition, as Chris Dixon points out in a recent podcast, software continually changes in ways which make the speed of product improvement a moat in and of itself [6].

Data: software & data-driven businesses provide more information about the end-customer than companies have ever had before. For instance, a retail store might know which customers live in the neighborhood and which are out-of-town visitors, how much they spend per week, socio-economic status, and likelihood of repeat purchases. All of these features, in effect, can narrow the probabilities around future store profitability and thus reduce future uncertainty.

Incorrect heuristics: what if diminishing returns no longer apply?

The law of diminishing returns and regression to the mean are deeply embedded in the value investing mindset, probably best summarized by the first page of Benjamin Graham’s Security Analysis:

Many shall be restored that are now fallen and many shall fall that now are held in honor.

For most value investors paying a high p/e multiple for a business is in effect a bet against probabilities: a study by Michael Goldstein at Empirical Research, a research boutique, claims that the probability of growth stock failure (company growth slowing) is as high as four in five over five years and nine out of ten over ten years [7]. Business characterized by network effects, however, are driven by increasing returns to scale. A recent Fast Company article excerpted W. Brian Arthur's idea as follows:

Increasing returns are the tendency for that which is ahead to get further ahead, for that which loses advantage to lose further advantage. They are mechanisms of positive feedback that operate—within markets, businesses, and industries—to reinforce that which gains success or aggravate that which suffers loss. Increasing returns generate not equilibrium but instability: If a product or a company or a technology—one of many competing in a market—gets ahead by chance or clever strategy, increasing returns can magnify this advantage, and the product or company or technology can go on to lock in the market. More than causing products to become standards, increasing returns cause businesses to work differently, and they stand many of our notions of how business operates on their head.

In the language of a discounted cash flow model, such a large, fast-growing business would tend to get larger and more profitable over time. Valuation heuristics that assume the opposite could be dangerously wrong.

Data / model-driven businesses magnify network effects

Many businesses exhibit characteristics of network effects that seem to extend beyond W. Brian Arthur's original definition. In his 1989 paper he described "network-effect" businesses whose underlying product became more valuable the more people used it. Cloud distribution, crowd-sourced data, and continually updating software may further extend that model. Some recent examples include the valuation of Xero, an cloud accounting software provider whose product benefits from the classification of transactions by millions of users. Or Alphabet’s Moonshot cybersecurity project which crowdsources valuable intrusion data to rapidly improve enterprise security: we know this works, Gmail’s spam filters are some of the best in the world. In each of these businesses, more data creates a better product, which drives more customers and repeat customers.

Paradoxically, the probability of continued success does not decline with greater size but rather increases. Software amplifies returns to scale in the same way the frictional costs of geography, people management, and working capital acted as an anchor on the proliferation of widget manufacturing in the physical world.

In some recognition that these insights are not unique Steven A. Cohen, the founder of the one of the largest hedge funds in the world, wrote an Op-Ed article in the WSJ recognizing the dominance of model-driven businesses relying on big data.

Incomplete GAAP financial disclosure

One of the most successful value investors of the last decade is Nicholas Sleep of Nomad Partnership, a relatively unknown investor. Two of his largest positions over this period were Amazon.com and Costco Wholesale, which trade at optically high earnings multiples.

One of Sleep’s insights was the recognition that both Amazon and Costco continually invested in lower consumer prices thus artificially depressing reported net profit. What GAAP accounting failed to recognize is this price-investment resulted in customers which stayed with the company for years and further entrenched their competitive advantage versus competitors.

When retail businesses that operate in the physical world invest in new stores we associate some value with this investment and the increases sales per square foot it might drive. But when companies invest in lower prices, or research & development, or spend more marketing dollars to increase repeat customers, GAAP accounting treats these investments as an expenses:

Business students are taught to value a company based on the discounted amounts of future cash flows or earnings. That concept is becoming almost impossible to apply to emerging companies that are run as a portfolio of ideas and projects, each with uncertain lottery-like payoffs. CFOs of these companies themselves admit that they cannot justify their market capitalizations based on traditional metrics. They conjecture that their market values might be the sum of the option values of the projects undertaken, a sum of best-case scenario payoffs. One CFO said that her valuation should be considered on a per idea basis instead of a per earnings multiple.

Some of this value would be captured in the equations for the valuation of software / SaaS businesses through customer lifetime value (CLTV), churn, contribution margin and customer acquisition costs (CAC). There seems to be some convergence in academic thinking between this idea of increasing returns to scale, intangible investment, and antiquated accounting standards:

In the 2016 book The End of Accounting, NYU Stern Professor Baruch claimed that over the last years or so, financial reports have become less useful in capital market decisions. Recent research lets us make an even bolder claim: accounting earnings are practically irrelevant for digital companies. Our current financial accounting model cannot capture the principle value creator for digital companies: increasing return to scale on intangible investments.

This article is only one of many which has began to recognize these defects. GAAP accounting has no way to describe this intangible investment yet the collective effects of these investments is to make both businesses appear to trade at disproportionate prices relative to their accounting profits.

V. Investment implications

This essay attempts to reconcile two seemingly contradictory ideas: a value-investors belief that 15x p/e stocks are reasonable and 30x p/e stocks are expensive, and recognition that the business model of software may change the incremental economics and future predictability of business. A value investors’ natural preference for cheaper p/e stocks partly reflects an unstated assumption of a world characterized by diminishing returns to scale.

Maybe the correct answer exists somewhere in-between: investors must incorporate the myriad of additional SaaS (software-as-a-service) data available in determining the intrinsic value of businesses. Like Nick Sleep’s framework for Amazon.com and Costco the most appropriate use of this mental model of software may be to recognize it applies infrequently, but when true, it explains business valuations that fall far outside the norms of what we’ve historically considered.

As recent events at Tencent and Facebook have shown, as much as software may have changed the economics of business, it has not changed the unpredictability of customer preference, government regulation, or the regular transitions between operating platforms. On this last point, I was recently reminded how dominant AOL instant messenger was 10-years ago. Yet the software service never successfully made the transition from desktop to mobile, despite its considerable user base and network effects.

In a recent interview John Hempton of Bronte Capital, an unconventional investment thinker, mentioned something interesting: maybe the economics of the software economy have been true since 2000, interrupted by a value rally in-between. W. Brian Arthur's concept of network effects were used to justify the valuation of many dot-com companies -- perhaps this was simply an idea ahead of its time.

Special thanks to B.C., K.P., A.L., N.L., J.K., T.M., H.P., E.S., B.K. and others for valuable feedback on these ideas over many conversations.